how are viruses different from bacteria apex: In the realm of infectious diseases, Nipah virus (NiV) emerges as a formidable adversary. It’s not just any virus; it’s a zoonotic virus, meaning it can leap from animals to humans. Moreover, it doesn’t stop there; it can also make its way into our lives through contaminated food or even direct human-to-human transmission. This makes NiV a double-edged sword in the world of pathogens. When it infects humans, it doesn’t stick to one playbook either, causing a spectrum of ailments ranging from asymptomatic (subclinical) infections to acute respiratory illnesses and, in its most sinister form, fatal encephalitis. But it’s not just humans who bear the brunt; NiV can wreak havoc among animals like pigs, inflicting significant economic losses on farmers. In this article, we’ll navigate the complex world of Nipah virus, where perplexity and burstiness intertwine.

Concern for Nipah Virus Public Health: The Brooding Threat

Though Nipah virus outbreaks have been relatively few in number, they resonate deeply in the annals of infectious diseases. This virus possesses an uncanny ability to infect a wide array of animals and, most alarmingly, induce severe disease and death in humans, thus earning its status as a looming public health concern.

Past Outbreaks: Distant Echoes

Nipah virus first came into our awareness in 1999 during a harrowing outbreak among pig farmers in Malaysia. Fortunately, no new outbreaks have been reported in Malaysia since that fateful year. However, the story takes a different turn in Bangladesh, where the virus made its presence felt in 2001 and has continued to haunt the country with nearly annual outbreaks. Periodic appearances of the disease have also been recorded in eastern India.

Beyond these known locations, the specter of Nipah virus looms in other regions. Evidence of the virus has been detected in its natural reservoir, the Pteropus bat species, and several other bat species in countries as diverse as Cambodia, Ghana, Indonesia, Madagascar, the Philippines, and Thailand.

Game of the Sneaky Transmission

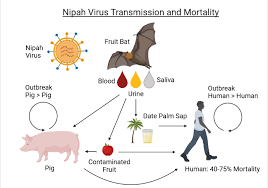

Transmission is where Nipah virus showcases its knack for versatility. During the initial outbreak in Malaysia, which also spilled into Singapore, most human infections sprouted from direct contact with ailing pigs or their contaminated tissues. It’s believed that transmission occurred through unprotected exposure to secretions from these swine or via contact with the tissues of sick animals.

However, subsequent outbreaks in Bangladesh and India took a different route. Here, the consumption of fruits or fruit products, often contaminated with urine or saliva from infected fruit bats, emerged as the primary source of infection. Astonishingly, no studies currently shed light on the virus’s persistence in bodily fluids or the environment, including fruits.

Notably, Nipah virus doesn’t always need an animal intermediary. Human-to-human transmission has been reported, particularly among family members and caregivers of infected patients. In Siliguri, India, in 2001, the virus even spread within a healthcare setting, with 75% of cases occurring among hospital staff or visitors. From 2001 to 2008, roughly half of reported cases in Bangladesh resulted from human-to-human transmission through providing care to infected patients.

Symptoms are revealed

Human infections with Nipah virus paint a broad and unpredictable canvas of symptoms. It can range from asymptomatic infection to acute respiratory illness, and at its grimmest, fatal encephalitis.

Initially, infected individuals might experience fever, headaches, muscle pain (myalgia), vomiting, and a sore throat. These symptoms could then give way to dizziness, drowsiness, altered consciousness, and neurological signs signaling acute encephalitis. Some unlucky souls might also contend with atypical pneumonia and severe respiratory issues, including acute respiratory distress. In severe cases, encephalitis and seizures can swiftly usher patients into a coma, typically within 24 to 48 hours.

The incubation period, the time from infection to symptom onset, varies widely, believed to range from 4 to 14 days. However, outliers have reported incubation periods stretching as long as 45 days.

While most survivors of acute encephalitis make a full recovery, some are left grappling with lasting neurological consequences, such as seizure disorders and personality changes. A fraction of those who initially recover may experience relapses or delayed onset encephalitis.

The case fatality rate, the proportion of cases that result in death, stands between an alarming 40% to 75%. The variance in this rate hinges on local capabilities for epidemiological surveillance and clinical management during specific outbreaks.

The Diagnostic Conundrum

Diagnosing Nipah virus infection isn’t straightforward. Its initial symptoms are nonspecific, making it a diagnostic challenge during presentation. This diagnostic complexity poses significant hurdles in outbreak detection, infection control, and response measures.

The accuracy of laboratory results is also influenced by factors like the quality, quantity, type, timing of clinical sample collection, and the time taken to transport samples to the laboratory.

Diagnosis of Nipah virus infection typically relies on clinical history during the acute and convalescent phases of the disease. Main diagnostic tests include real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from bodily fluids and antibody detection via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Additional tests like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays and virus isolation by cell culture can also be employed.

A World Without Specific Drugs or Vaccines

Presently, there are no drugs or vaccines specifically tailored to combat Nipah virus infection. However, the World Health Organization (WHO) has identified Nipah as a priority disease under its Research and Development Blueprint. The primary mode of treatment recommended for severe respiratory and neurological complications is intensive supportive care.

The Enigmatic Natural Host: Fruit Bats

Fruit bats, particularly those belonging to the Pteropus genus, are the natural hosts for Nipah virus. Remarkably, these bats appear unaffected by the virus, exhibiting no apparent disease.

The geographic distribution of Henipaviruses aligns closely with that of Pteropus bats. This connection is substantiated by evidence of Henipavirus infection in Pteropus bats from various countries, including Australia, Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Madagascar, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, Thailand, and Timor-Leste.

Even African fruit bats, specifically those in the Eidolon genus, within the Pteropodidae family, have tested positive for antibodies against Nipah and Hendra viruses. This suggests that these viruses might lurk within the geographical domain of Pteropodidae bats in Africa.

Nipah Virus in the Domestic Realm

The Nipah virus doesn’t restrict itself to the wild; it’s made unsettling appearances in domestic animals. During the initial Malaysian outbreak in 1999, the virus spilled over to pigs and other domestic creatures, including horses, goats, sheep, cats, and dogs.

Pigs, in particular, are highly susceptible to the virus, with their infectious period spanning the 4 to 14-day incubation period. Infected pigs can range from asymptomatic to exhibiting symptoms such as fever, labored breathing, trembling, twitching, and muscle spasms. While mortality is generally low, piglets, especially young ones, face a higher risk of succumbing to the virus. It’s worth noting that these symptoms can closely mimic other respiratory and neurological illnesses in pigs. Suspicions of Nipah virus arise if unusual signs like an atypical barking cough or the presence of human encephalitis cases coincide.

For more comprehensive information on Nipah virus in animals, consult the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations webpage on Nipah and the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) webpage on Nipah.

Overview

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Symptoms | – Fever – Headaches – Muscle pain (myalgia) – Vomiting – Sore throat – Dizziness – Drowsiness – Altered consciousness – Neurological signs – Atypical pneumonia – Severe respiratory issues – Encephalitis – Seizures – Coma – Incubation period: 4 to 45 days – Case fatality rate: 40% to 75% |

| Causes | – Zoonotic virus (transmitted from animals to humans) – Direct contact with infected animals (initial outbreaks) – Consumption of contaminated fruits from infected bats (later outbreaks) – Human-to-human transmission (especially among family members and caregivers) |

| History | – First identified in 1999 during an outbreak among pig farmers in Malaysia – Subsequent outbreaks in Bangladesh and eastern India – Evidence of presence in various countries via bats (Cambodia, Ghana, Indonesia, Madagascar, the Philippines, Thailand, etc.) – Ongoing public health concern |

| Natural Host | – Fruit bats, particularly Pteropus genus – Bats appear unaffected by the virus, serving as reservoirs |

| Diagnosis | – Challenging due to nonspecific initial symptoms – Relies on clinical history – Diagnostic tests: real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, virus isolation |

| Treatment | – No specific drugs or vaccines – Supportive care for severe respiratory and neurological complications |

| Prevention | – Control in pigs: cleaning, quarantine, culling, and movement restrictions – Public health measures: reducing transmission risks, protective gear when handling sick animals, hand hygiene – Infection control in healthcare settings |

| WHO’s Role | – Offers support to affected countries – Provides technical guidance on outbreak management and prevention |

| Global Collaboration | – Emphasizes a One Health approach involving humans, animals, and the environment in addressing infectious diseases |

The Imperative of Prevention

Preventing Nipah virus infection is a multi-pronged challenge.

- Controlling Nipah Virus in Pigs: In the absence of vaccines, effective control hinges on meticulous cleaning and disinfection of pig farms using appropriate detergents. In outbreak scenarios, immediate quarantine of animal premises is vital. Culling infected animals, with strict oversight of burial or incineration of carcasses, may be necessary to curtail transmission risk. Restricting or banning the movement of animals from infected farms can help contain the spread. Establishing animal health/wildlife surveillance systems that embrace a One Health approach is crucial for early detection.

- Reducing the Risk to Humans: In the absence of a vaccine, public health awareness and education take center stage. Messaging should revolve around reducing the risk of bat-to-human transmission, animal-to-human transmission, and human-to-human transmission. Precautions such as wearing protective gear when handling sick animals, avoiding close contact with infected pigs, and practicing regular hand hygiene after caring for sick individuals can mitigate risks.

- Infection Control in Healthcare Settings: Healthcare workers dealing with suspected or confirmed cases of Nipah virus infection should implement stringent infection control precautions. Given documented human-to-human transmission, contact and droplet precautions should be complemented by standard measures, with airborne precautions possibly necessary in certain scenarios. Trained staff in suitably equipped laboratories should handle samples taken from individuals and animals with suspected Nipah virus infection.

WHO’s Vigilant Stance

The World Health Organization (WHO) is on the frontlines, offering support to countries affected by or at risk of Nipah virus outbreaks. WHO provides critical technical guidance on outbreak management and prevention strategies.